10. Carver Heights Motel

African American motel constructed in 1950 to cater to travelers in segregated Columbus, Georgia.

[image] PLAT OF SUBDIVISION HERE WITH COMMERCIAL AREA INDICATED

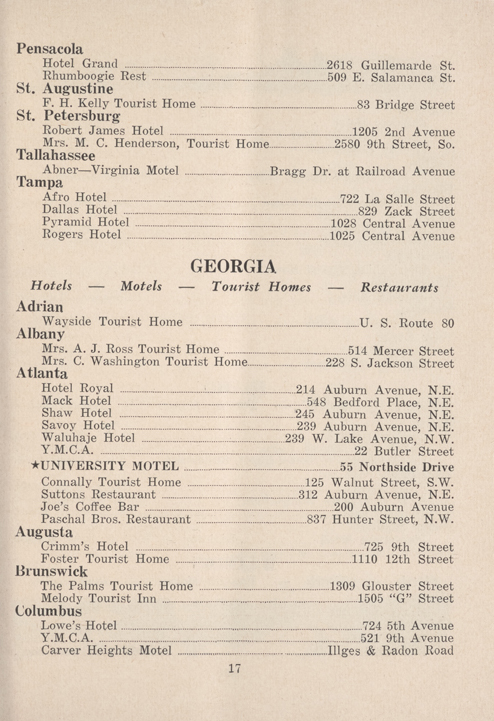

The Carver Heights Motel was constructed in 1950 in a segregated Columbus, Georgia. That year, real estate developer E. E. Farley began developing an African American subdivision of 207 lots in Columbus. Five of those contiguous lots became a small triangular commercial district on the western boundary of the subdivision at the intersection of Rigdon Road and Illges Road. It was soon the home of the small Carver Heights Motel offering African Americans’ 12 small ensuite rooms when traveling in the segregated South. Guests included not only vacationers but many African American entertainers in Columbus to perform at such venues as the Liberty Theater, auditoriums in the Sconiers or Odum buildings, or the Prince Hall Masonic Lodge.

The Carver Heights Motel was the third location in Columbus to provide lodging for African Americans. The other two were the Lowe’s Hotel at 724 5th Avenue and the African American YMCA a short distance away at 521 9th Street, both in the downtown commercial African American section of Columbus. The owners of the Carver Heights Motel may not have nationally advertised their existence to African American travelers until they published an advertisement in the 1956 Negro Motorist Green Book. That initial listing gave the address as “Illges and Radon (vice Rigdon) Road”

Jim Crow laws across the south coupled with an emerging and more mobile African American middle class lead Victor Hugo Green to begin publishing the Negro Travelers’ Green Book in 1936. That guide, with information organized by state and city, allowed travelers to locate relatively friendly access to lodging, food, and other necessary services. The initial volumes were focused on the New York area but soon covered much of the nation. Soon after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed, publication ceased in 1967, perhaps as travel became less challenging for African Americans during the transition to a more integrated nation. By 1975 the motel’s 12 small ensuite rooms were already being considered for repurposing with plans for one half to become a restaurant and the other half to become a beauty/barber shop. Only the plans for a barber shop on one end and a beauty shop on the other were fulfilled.

“Figure 1: 1956 Negro Travelers’ Green Book”

[insert image]1957 Green Book image here: TEXT: “Figure 2: 1957 Negro Travelers’ Green Book”

Submission composed by Joyce Wade, April 3, 2017

References and Further Reading

Green, V H. 1956. “The Negro Travelers’ Green Book.” New York: Victor H. Green & Company. (Available at https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/collections/the-green-book#/?tab=about) (Accessed on April 1, 2017)

James-Johnson, A. 2013 “City planners create vision for MLK Boulevard.” (Available at http://www.ledger-enquirer.com/news/local/article29296711.html ) (Accessed on April 1, 2016)